Irish Linen: An Odyssey from Milwaukee

Ashley Bohne (she/her) is a fourth year BFA candidate with a dual focus in Fibre and Jewellery, and Metalsmithing at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. Her love for fibre and interest in female-dominated craft began at a young age when she learned how to sew from her grandma. She works with fibre and metal, and uses traditional ways of making (weaving, metal fabrication, sewing, enamelling) to challenge its boundaries. Her work explores the longevity of handcraft and the continuation of generational knowledge that has been lost.

As part of her artistic practice, and funded by the Center for Craft Windgate Lamar Fellowship, she travelled to Ireland to dive into the history and process of taking the flax plant all the way to linen. We were delighted that her visit overlapped with the Linen Biennale 2023 and asked her to write about her journey and some of the discoveries made along the way.

“Remnants”, Ashley Bohne, UWM Kenilworth 3rd Floor Gallery UWM, 2023

Irish linen is known throughout the textile world as one of the most luxurious textiles produced to this day. To be marked the prestigious “Irish Linen”, its thread is required to be made from 100% flax fibers, and when woven is required to use 100% linen. The industry originated in Ireland in the late 17th century, when many skilled weavers from France moved to Ireland bringing their skills with them. Upon realizing the potential for this product, many farms began growing flax, processing it all by hand up until it was the beautiful white fabric we know. However, as time progressed the industry became industrialized, moving from hand processing, spinning, and weaving to large machines and factories. Fast forward to today, the beginning stages of linen are almost entirely depleted, only the weaving still done within Ireland.

Preserved Traditional Houses, Ulster Folk Museum.

Photo: Ashley Bohne 2023

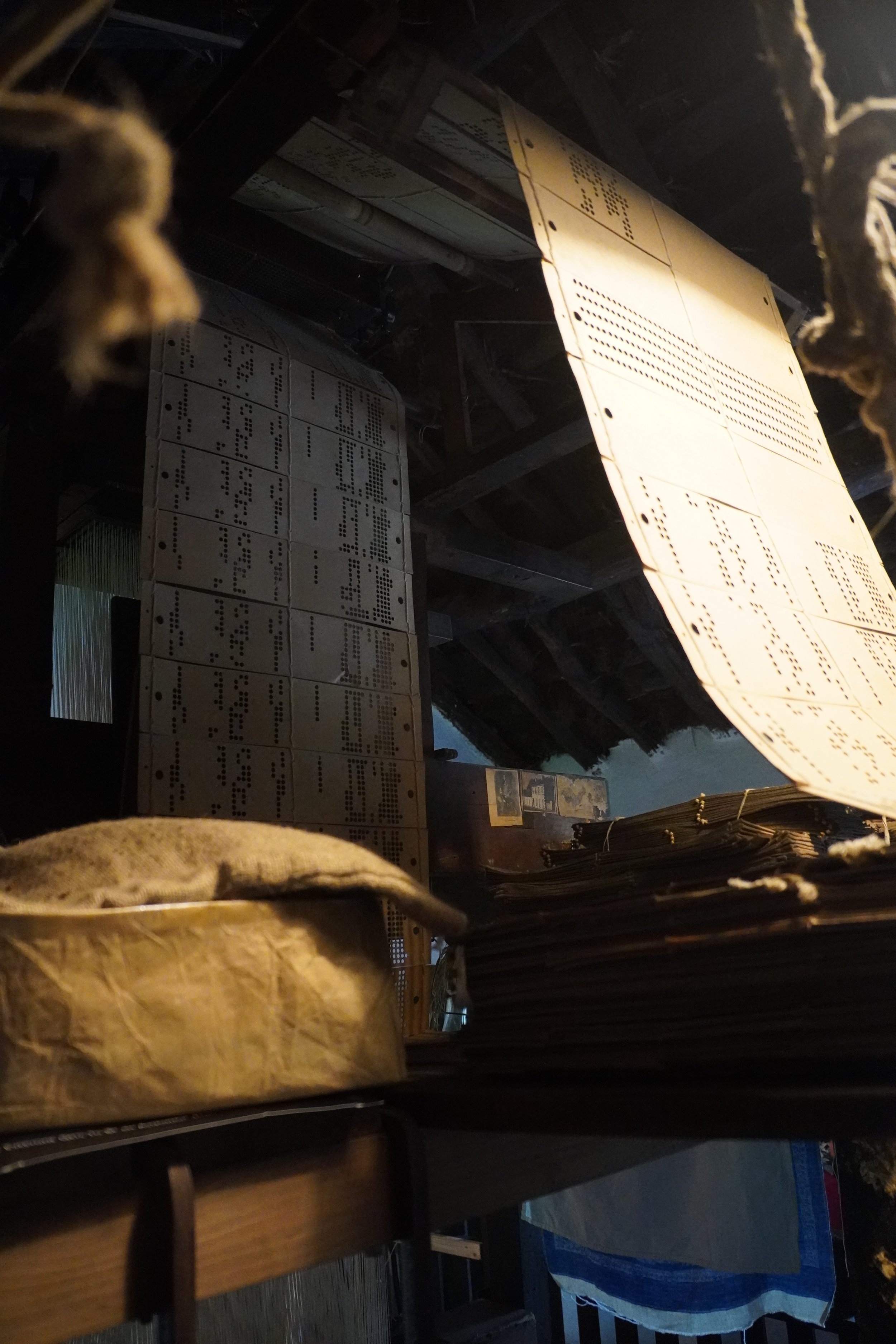

I began my research at the heart of the Irish Linen industry, Belfast, by travelling to the Ulster Folk Museum, an open-air museum experience which is home to a rich collection of heritage buildings and objects. These buildings and objects include a wool and linen weaver’s cottage, complete with operating Jacquard looms dating back to the 1860s. The preserved house depicts a typical layout of the home of a weaver, with a dedicated room for weaving attached alongside the house, as well as spinning and winding wheels throughout. It was here I was given a brief history of the linen industry and introduced to the generational connections that a large majority of people have to the industry. Due to Belfast being one of the largest Linen producers in the country, many people still have some connection to the industry. Whether it be a taxi driver I met whose mom worked in a winding mill, or the hotel owner whose grandfather owned a weaving mill, connections were constantly being made when I shared the purpose of my visit. These ideas of generational knowledge are perhaps written better in the museum's own words:

“The museum offers a place to think about how we, as the current generation, are still adapting to change and how we might find meaning and inspiration from the many generations before us to help build a cleaner, greener and prosperous future.”

Jacquard motor reading weaving patterns.

Photo Ashley Bohne, Ulster Folk Museum, 2023

The next destination in my research was the Lisburn Irish Linen Centre. The permanent exhibit “Flax to Fibre” was an amazing collection walking you through the history of linen production in Ireland, as well as a thorough walkthrough of the fiber process.

As you walk through the exhibit it takes you through the various laborious steps of flax processing, beginning with harvesting, retting, and breaking. The flax plant is pulled from the ground roots and all, then dried before being put through a smelly process called retting. Retting consisted of laying bundles of flax in a body of water and weighing them down with heavy rocks. The water helps to break down the fibers within the plant making them softer, and separating the fiber from its more rigid outer shell. This process resulted in a large amount of chemical contaminants in the Irish waterways, so now is done in large tanks where the water can be disposed of appropriately. Once removed from the water and property dried, the plant goes through a process called scutching, where a wooden beater beats down on the plant to break away the hard outer shell and reveal the fine fiber in the middle. When done by hand, it is a laborious and time-consuming process, so it was quickly made semi-mechanised by water-powered mills, that would power rolled allowing for heavy wooden blades to drop down.

Refurbished Mackie’s Scutching Turbine,

Mallon Linen, Ashley Bohne, 2023

The final step, hackling, was done by combing the course fiber through various densities of iron spikes. The combing would detangle the fibers, as well as create a silky, smooth texture. Again, this was a time-consuming and laborious process and was quickly industrialized to increase production.

At one time, over 800 linen mills populated Ireland, and now, only a few remain in various parts and pieces. One piece of this production history lies at Mallon Linen in Cookstown, Northern Ireland. Run by Helen and Charlie Mallon, they own and operate a 1940s Mackie's scutching turbine (pictured) completing the last two processes (scutching and hackling) in a matter of minutes. Completely refurbished, the turbine is run by a series of motors, allowing for a quicker turnover of fiber while remaining almost carbon neutral. I was able to work with this machine for two days, in charge of laying out the flax stalks to be fed into the machine.

After working with Helen processing the flax, I was able to join her for a talk at the Belfast Print Workshop, which was part of the Linen Biennale programme. Helen spoke on the process I had spent the past few days helping with, as well as continuing the ideas of sustainability and creating a circular chain of linen production within Ireland. I was also able to speak briefly about my own work and its connections to linen.

Looking at flax and linen production, flax is a zero-waste product, and the entire plant is utilized for a variety of products. Flax seeds are used for flax seed oil or food, the plant fiber is used for a variety of products, and even the outer shell can be used as a mulch or hay for farms. Traditional hand-processing methods also emit little to no harmful emissions, and even with the large scutching machine running on motors, Mallon Linen is able to operate at almost carbon neutral. This obviously changed immensely when the process was industrialized and heavy fossil fuel-dependent machinery became responsible for the production. This led not only to tonnes of toxic emissions and waste but also disrupted the cycle of generational knowledge that had maintained the craft thus far.

Image left – Mason, Thomas Holmes. “Smyth’s Cottage Industry. Mother/Daughter Working at Home,” 1910 1890. Mason Photographic Collection.

A very important aspect of the linen industry in Ireland is the generational history behind its production. When the industry first began, it was primarily a domestic industry, with entire households dedicated to the production but producing enough to provide for the family. In addition, the local economy ran in a very circular fashion, people trading goods for what was needed, with less excess and in turn less waste.

However, once it was realized the profit that could come from producing linen in larger volumes, these ideas were changed from those of sustainabiliy and community to profit and wealth. This shift in generation ideals not only contribute to a capitalist mentality, damaging the environment and its people all over the world, but result in an almost complete loss of the traditions. Within my own work, I see sustainability as a presence that goes hand-in-hand with fiber and textile work in its utilization of plant materials and look to generational history to inform these ways of making. Working primarily with natural fibers, specifically linen, when contrasted with a longer-lasting material like metal, instigates questions of longevity. Longevity is not only in the literal sense of the material but also in the longevity of its practices over generations.

Thanks Ashley for sharing some your journey with us! It is great to see our heritage from new perspectives and we can’t wait to see how your work developes from the experiences you had.

Keep up with Ahsley’s work via her Website or Instagram page.